In July 1994, a talented South African photojournalist sat in his red pickup truck in Johannesburg, overwhelmed by the weight of what he had witnessed. “I’m really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist,” wrote Kevin Carter in his suicide note before succumbing to carbon monoxide poisoning. He was just 33 years old, and only four months had passed since winning journalism’s highest honor.

The image that earned Carter the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography depicts a scene of heartbreaking desperation: a starving child collapsed on the ground, struggling to reach a food center during a famine in the Sudan in 1993, with a vulture stalking the emaciated child in the background. Carter had captured this devastating moment during the 1993 Sudan famine, in what relief organizations called “The Hunger Triangle” — the area defined by the southern Sudan communities of Kongor, Ayod, and Waat.

The photograph, published in The New York Times in March 1993, immediately shook the world with its raw portrayal of human suffering. The stark imagery — the skeletal frame of a child bent over in exhaustion, the predatory bird waiting ominously in the background — conveyed the horror of the famine more powerfully than any written account could.

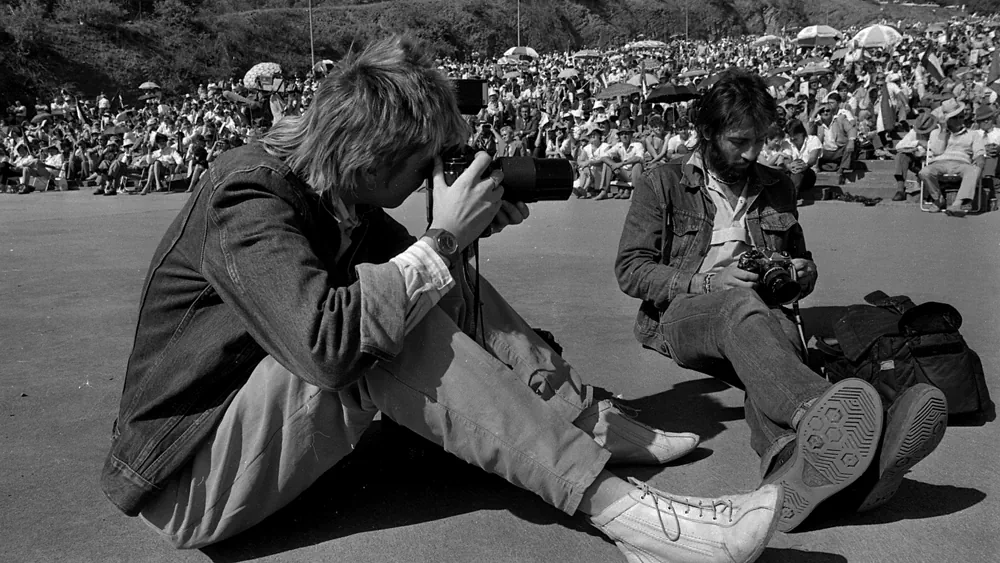

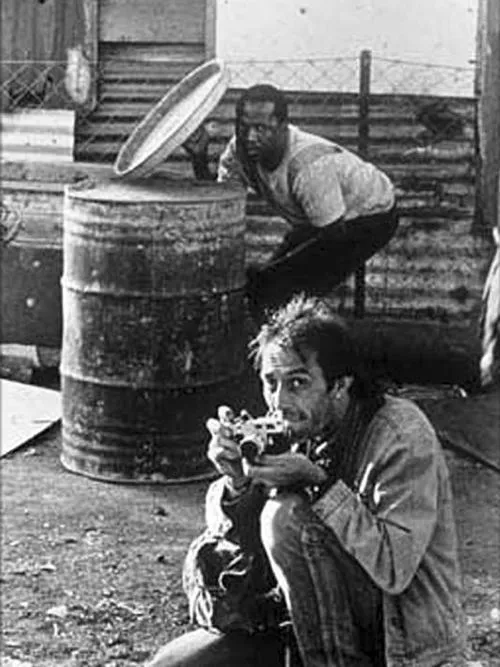

The Man Behind the Camera

Kevin Carter was no stranger to documenting human suffering. He was part of a group of four fearless photojournalists known as the “Bang Bang Club” who traveled throughout South Africa, capturing the atrocities committed during apartheid. These photographers risked their lives daily to bring the world’s attention to injustice and human rights violations.

Carter had witnessed countless scenes of violence and despair throughout his career, but the Sudan assignment proved to be different. The famine’s severity jolted him. At the camp, he photographed an emaciated girl collapsed on the ground, with a vulture ominously nearby. This single moment would define both his most significant professional triumph and his personal downfall.

When Carter’s photograph won the Pulitzer Prize in April 1994, it should have been the pinnacle of his career. Instead, it became a source of profound anguish. The recognition came with intense scrutiny and criticism from around the world. A wide range of people in society criticized Carter for using the girl to take pictures instead of helping her, with people angry about his “patience” to wait 20 minutes before he helped the girl.

The ethical questions surrounding the photograph haunted Carter. Critics demanded to know why he hadn’t immediately helped the child, what happened to her after the photo was taken, and whether it was morally acceptable to document such suffering without intervening. Though Carter later explained that he had chased the vulture away and that the girl had reached the feeding center, the damage to his psyche was already done.

Those social judgements, along with the abysmal scenes Carter had been dealing with his whole life, finally struck him down. The photographer, who had dedicated his career to exposing the world’s injustices, found himself unable to bear the weight of what he had witnessed and the criticism that followed his most outstanding achievement.

Carter’s story represents one of journalism’s most tragic paradoxes: the very sensitivity and empathy that drove him to document human suffering also made him vulnerable to the psychological toll of his work. His photograph succeeded in its purpose — it brought global attention to the Sudan famine and likely helped mobilize aid efforts. Yet the personal cost to the man behind the lens proved unbearable.

The story of Kevin Carter and “The Vulture and the Little Girl” remains a powerful reminder of the human cost of bearing witness to the world’s darkest moments. It raises enduring questions about the ethics of photojournalism, the responsibility of those who document suffering, and the psychological support needed for those who risk everything to bring us the truth.

Carter’s legacy lies not just in a single, devastating photograph, but in his commitment to showing the world what it would rather not see. His tragedy reminds us that behind every powerful image is a human being, often carrying burdens far heavier than we can imagine. In our quest to understand the world through the lens of photojournalism, we must also remember to understand and support those who sacrifice their peace of mind to illuminate our collective conscience.